Understanding is a poor substitute for Convexity (Anti-fragility)

Chance or trial and error cannot be effective in the long run

…neither trial and error nor “chance” and serendipity can be behind the gains in technology and empirical science attributed to them. By definition chance cannot lead to long term gains (it would no longer be chance); trial and error cannot be unconditionally effective: errors cause planes to crash, buildings to collapse, and knowledge to regress.

Contradiction: Past results are thought to be due to chance and yet future plannings are done with direction!

This makes us live in the contradiction that we largely got here to where we are thanks to undirected chance, but we build research programs going forward based on direction and narratives. And, what is worse, we are fully conscious of the inconsistency.

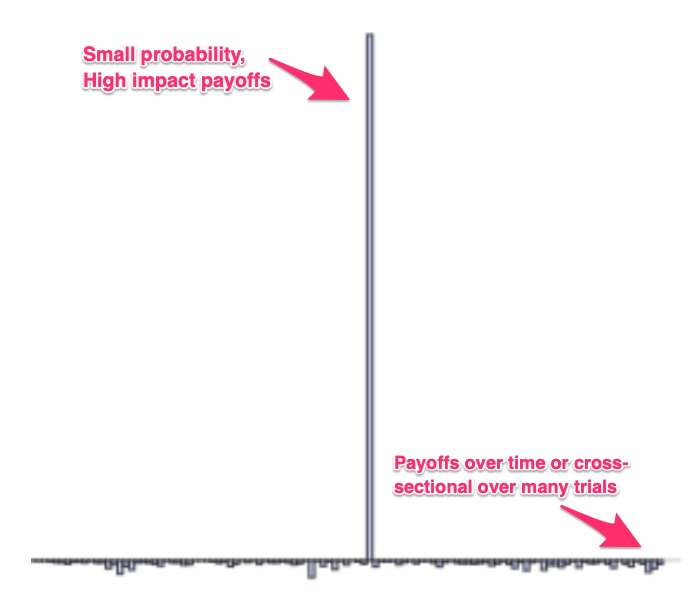

Design for convexity so that you are harmed less by an error and benefit when there is a positive return

Critically, convex payoffs benefit from uncertainty and disorder. The nonlinear properties of the payoff function, that is, convexity, allow us to formulate rational and rigorous research policies, and ones that allow the harvesting of randomness… The implication is that you are harmed much less by an error (or a variation) than you can benefit from it, you would welcome uncertainty in the long run.

Convexity allows us the option, not obligation to keep the results

Critically we have the option, not the obligation to keep the result, which allows us to retain the upper bound and be unaffected by adverse outcomes. This “optionality” is what is behind the convexity of research outcomes. An option allows its user to get more upside than downside as he can select among the results what fits him and forget about the rest (he has the option, not the obligation).

Why evolution is an example of a convex function?

…evolution is a convex function of stressors and errors — genetic mutations come at no cost and are retained only if they are an improvement. So are the ancestral heuristics and rules of thumbs embedded in society; formed like recipes by continuously taking the upper-bound of “what works”. But unlike nature where choices are made in an automatic way via survival, human optionality requires the exercise of rational choice to ratchet up to something better than what precedes it —and, alas, humans have mental biases and cultural hindrances that nature doesn’t have.

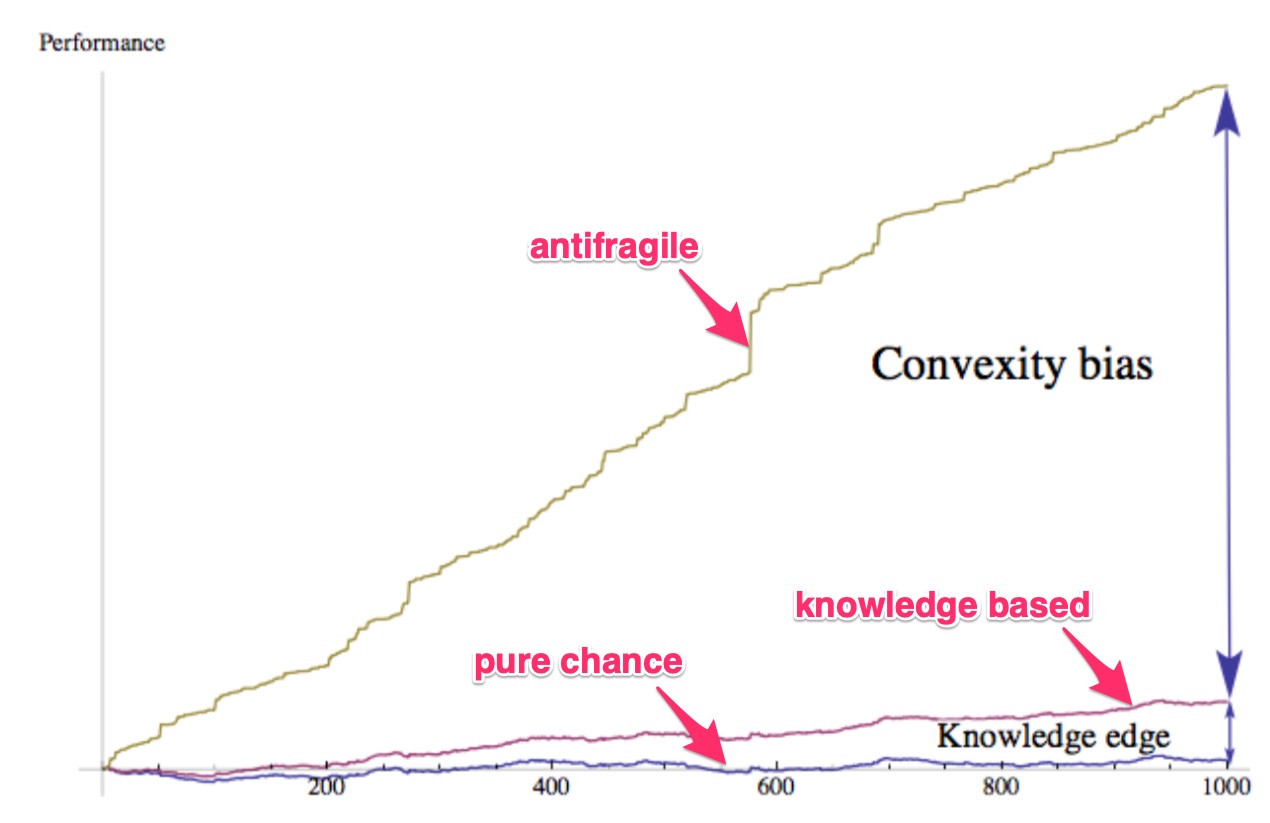

Convexity bias

Let us call the “convexity bias” the difference between the results of trial and error in which gains and harm are equal (linear), and one in which gains and harm are asymmetric (to repeat, a convex payoff function). The central and useful properties are that a) The more convex the payoff function, expressed in difference between potential benefits and harm, the larger the bias. b) The more volatile the environment, the larger the bias. This last property is missed as humans have a propensity to hate uncertainty.

How convexity bias can be used

The convexity bias, unlike serendipity et al., can be defined, formalized, identified, even on the occasion measured scientifically, and can lead to a formal policy of decision making under uncertainty, and classify strategies based on their ex ante predicted efficiency and projected success.

How convexity can be increased?

…under some level of uncertainty, we benefit more from improving the payoff function than from knowledge about what exactly we are looking for. Convexity can be increased by lowering costs per unit of trial (to improve the downside).

1/N strategy

A “1/N” strategy is almost always best with convex strategies (the dispersion property): following point (1) and reducing the costs per attempt, compensate by multiplying the number of trials and allocating 1/N of the potential investment across N investments, and make N as large as possible. This allows us to minimize the probability of missing rather than maximize profits should one have a win, as the latter teleological strategy lowers the probability of a win.A large exposure to a single trial has lower expected return than a portfolio of small trials.

Serial optionality

Serial optionality (the cliquet property). A rigid business plan gets one locked into a preset invariant policy, like a highway without exits — hence devoid of optionality. One needs the ability to change opportunistically and “reset” the option for a new option, by ratcheting up, and getting locked up in a higher state. To translate into practical terms, plans need to 1) stay flexible with frequent ways out, and, counter to intuition 2) be very short term, in order to properly capture the long term. Mathematically, five sequential one-year options are vastly more valuable than a single five-year option.

Why strategic planning fails

This explains why matters such as strategic planning have never born fruit in empirical reality: planning has a side effect to restrict optionality. It also explains why top-down centralized decisions tend to fail.

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” - Thomas Edison

Better cataloguing of negative results (the via negative property). Optionality works by negative information, reducing the space of what we do by knowledge of what does not work. For that we need to pay for negative results.